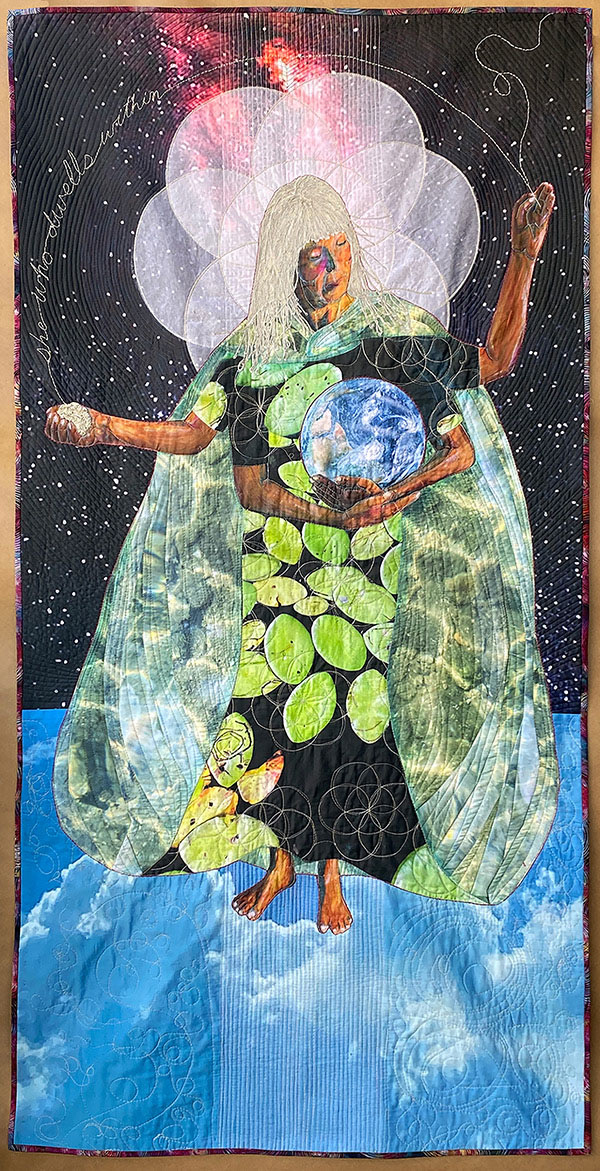

Artist Statement: This is the third in a series of art pieces in which I endeavor to illuminate the lost, obscured and

manipulated sacred feminine from the Judeo/Christian pantheon.

To begin, I want to acknowledge that I am not a scholar of religion. What I have brought

together is gleaned from reading and conversations and my own belief that expressions of the

Sacred Feminine existed in the past, are available in the present and are crucial for a more

inclusive future. That said, here is what I have gathered to add to my conviction.

Judaism arose at a certain moment in cultural history. For tens of thousands of years before the

rise of Judaism, the Great Mother was the central figure of Divinity throughout many traditions.

Images of the Great Mother deity from the fertile crescent area of the near east represent her

in the presence of a sacred tree, often accompanied by a serpent. Sound familiar? In the first

millennium B.C.E. the Goddess Kali arose in the Hindu tantric tradition, as mother of the

universe and all living beings, the giver of life and death, the arbiter of transformation and

revolution. Kali is depicted as a multi-armed woman meting out justice both violent and

nurturing. In this milieu the worship of the Goddess Asherah from Canaanite pantheon was

evident in the earliest stages of Judaism and was widespread in villages and sacred tree groves

throughout ancient Israel. Asherah was symbolized by poles that were sunk deep into the

earth, denoting the ground from which all life springs. Small figurines were planted in sacred

groves, symbolizing the peoples’ prayers for fertility in their crops and families.

As Judaism evolved it moved away from depicting the divine in representable form and the

worship of Asherah figures eventually were abandoned and banned as objects of idol worship.

Within this context the concept of Shekhinah emerges. Shekhinah is a Hebrew word describing

the manifestation of God's presence on earth in feminine terms. Shekhinah can be translated as

she who dwells within. She is the part of God that does not leave us. She is the guide for the

people in exile; she is said to be in the pillar of clouds by day and the pillar of fire by night that

guides the Israelites out of Egypt. She is the flame of the burning bush and the cloud on Mount

Sinai that Moses beheld. She who dwells within is our inner flame, she is always there to guide

us when we come seeking.

I see her in the ancient earth goddess figurines of cultures known and unknown. I see her in the

Hindu goddess Kali, I see her in the Asherah figurines of early Canaanite peoples. In the

Christian context I see Shekhinah in the Holy Spirit and most approachably in Mary the mother,

nurturer, and caregiver. Mary is often called upon to intercede on our behalf to a less

approachable, more remote, male depicted God figure. Shekhinah moves through them all.

Unfortunately, over place and time, mention of the sacred feminine has been redacted, erased,

and ignored from much of the Abrahamic religious readings, teachings and thought of Judaism,

Christianity, and Islam. Why this was done is a complicated question that is probably about

power and fear and a smallness of understanding. What I can do as an artist and a feminist who

participates in Christian life, is to try push the conversation, to rethink the perceptions. To

move beyond a binary choice of God being either male or female but both and more. I want my

art and its explanation not to be the answer but one of thousands and millions of depictions,

visions, and versions. When all the variations of experience of the vast power of the universe

that is called God are discussed, depicted, honored, revered, and revealed – then, and perhaps

only then - may we begin to come closer to understanding the true mystery and meaning that

can heal the earth and bring creation into balance.

My Shekinah is luminous and strong. She has four arms to suggest her capacity to embrace and

love beyond human knowing. In one set of arms, she nurtures and cradles the earth and us.

With the other set of arms, she holds a ball of thread and needle, forever stitching back into

balance the world we have damaged. Stitched in an arch of silver thread reaching from hand to

hand are the words she who dwells within which is a translation from the Hebrew of the name

Shekhinah.

The image on her dress is of water and lily pads invoking the dark mystery below the surface

and the knowable floating right there for us to see and touch. She has a winged cloak with

images of sparkling light reflecting on the rippling shallow water coursing over river stones just

below the surface to hint at the extraordinary within the ordinary. She floats in a pillar of clouds

at her feet and a pillar fire represented by stars of the distant cosmos above her, this is a

reference to Shekhinah as the guide and guardian of the Israelites in their exodus from Egypt in

the Hebrew bible. Behind her head are seven overlapping circles that create a pattern called

the seed of life. From the concept of sacred geometry this pattern symbolizes the seed of

creation from which all life resides, where life begins and returns. The seed of life pattern is also

stitched into Shekhinah’s dress with silver threads.

She is embodied in the figure of an older woman, silver haired and radiant - full of wisdom,

understanding and persistence. I have chosen the quilt as art medium for a reason. For me, the

use of fabric and stitch is connected to the act of being a doer and maker. It is something I

learned from my foremothers; the way that making a bedquilt, a garment or meal could be

both a necessity of life and a creative expression. Here I use the quilt form, that is rooted in

warmth and comfort, as the canvas for Shekhinah. She who dwells within – always there when

you chose to seek her.

This summary is greatly informed by two main sources. Rabbi Leah Novick’s book On the Wing

of Shekhinah: rediscovering Judaism’s Divine Feminine and the text of a lecture given by

Shaoshanna Fershtman at the Mendocino Coast Jewish Women’s Retreat in 2018. Also thank

you to my niece Francesca Rubinson, a grad student at Harvard Divinity School, for her scholarly

insights and to my friend Sonia Beck Doss for sharing her perceptions on Shekhinah and for

being my physical model. And finally, to my sister Laura Thorpe for being my hand model and

my biggest fan.

Bio: As an artist I am an explorer and observer first. I like to wander and

wonder, let things percolate while I ponder. I have numerous sketchbooks full of

chicken scratch drawings and cryptic thoughts. Over time (and often during a

long hot shower) an idea will keep rising to the surface, I might even push that

thought bubble below the surface, telling it I don’t have time for you, but the best

ideas won’t pop and so I move on from thought to action. I like to problem solve,

to piece and play with an idea until it can take shape as a visual idea. I love the

mess of dyeing, printing and marking my own fabric. I scan my collection of photos

in my phone to print on fabric and weave into my work. I like to transform the

everyday observations of delight and wonder from my life to the meaning driven

intent of my art quilts. I am drawn to the use of fabric and stitch as a reference to the

tradition of stitch as a feminine art that clothes and covers and comforts. It is

something I learned from my foremothers; the way that making a bedquilt, a

garment or meal could be both a necessity of life and a creative expression.

Over the years I have been a painter, a printer, a graphic designer, and

collage maker, but the medium that keeps calling me back is fabric and stitch. My

visual work is idea and story driven and often connected to words and writing and I

feel the long thread of connection between textile work and words. The etymology

of the words textile and text come from the same Latin root, texere, meaning “to

weave”. The art I make is about weaving a story, some are as complex as the story of

the Eve in the Garden of Eden, others are a as simple as a single phrase “Ask

Nothing”. Whatever medium I work in, I’m weaving a story for the viewer to step

into. The art is both personal and universal. Driven to pique and poke and ponder,

my work invites discussion and discovery and as an educator I like to participate in

forums and publications to explore and explain my work within the context of

feminist, spiritual and environmental themes.

Website: lisathorpe.com

|